Once upon a time, politicians paid lip-service to the idea that our country should operate with some semblance of fiscal responsibility. It’s almost comical to look back at Ross Perot’s presidential runs in 1992 and 1996 when he used flip charts to rally against government debt.

Back then the United States had a national debt of $4-5 trillion, about 65% of GDP. Today the national debt is $23 trillion and equals about 105% of GDP.[i]

What once seemed impossible—the United States defaulting on its debt—is now all but certain. The United States has no other realistic path but to default. In fact, it has already started.

Looking Back

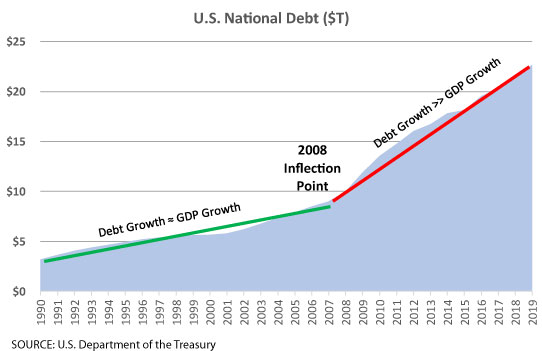

Perhaps Perot’s lectures worked. From 1992 until 2007, the national debt grew roughly in line with GDP growth.

But once the 2007-2008 financial crisis hit, the combination of increased government spending and lower revenue swelled the deficit to almost $2 trillion for 2009 alone.

Unlike other recessions, the government kept spending significantly more than it was receiving in tax revenue once economic growth resumed. As a result, the national debt increased by more than $1 trillion during 7 of the past 10 years[ii] of economic expansion (2010-2019).

Congressional (In)Action

Before the 2016 election, there was a breed of politicians in Congress that spoke out about the dangers of the increasing debt and the need to control spending (or raise additional revenue). Congress even passed the Budget Control Act of 2011 that had built-in across-the-board cuts in spending if congress failed to agree on specific cuts—and fail they did.

This failure to identify specific reductions, resulted in automatic budget limitations starting in 2013 known as budget sequestration. Sequestration helped slow the growth in spending for a few years, although Congress systematically undermined the bill over time. Ultimately, the 2018 budget more or less eliminated the impact of sequestration on controlling government spending.

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017—which materially reduced tax revenue—and disregard for agreed spending limits, has left us with annual trillion-dollar plus deficits with no end in sight.

There is no appetite in Congress (or among those running for President in 2020) to make any changes that would restore fiscal balance. Those who want to raise taxes also want to introduce new spending that would exceed the increased revenue. And those who like the current tax rates, have shown no interest in reducing spending (as demonstrated by the significant increases passed for 2018 and 2019).

Failure

Traditionally the concept of defaulting on a debt means the issuer fails to meet an interest payment or fails to repay principal at the loan’s maturity. But when the issuer of the debt is a sovereign nation—that also controls the currency the debt was issued in—failure can take on other forms. The country can reduce the economic value of what bondholders are owed without technically missing a payment.

United States Treasury bonds are backed by the “full faith and credit of the United States.” This implies that any attempt by the government to reduce the promised payments or simply zero-out the obligation would be met with legal challenges, followed by a judgement against the government and potentially a lien on government assets until bond holders are paid.

This legal obligation is why Treasury bonds are often considered a risk-free asset. The assets of the United States (and the ability to tax its citizens) could repay even the $23 trillion we currently owe…although repayment would be painful (how much could we get for Yosemite National Park?)

But there are other options that have a similar impact—other ways the government can fail to fully pay its financial debts.

How to Default

One way would be to devalue the currency. Treasury bonds are generally issued at a fixed interest rate for a fixed time period; payable in U.S. dollars. If the government devalued the currency to 20% of its current value, the debt load would shrink in economic terms by 80%. Suddenly the crushing national debt wouldn’t be so bad.

It is not obvious how the U.S. Treasury could go about devaluing the currency, but one simplistic method would be to issue a “new dollar” that is exchangeable for one-fifth of an “old dollar” (current dollars). Effectively increasing the amount of dollars in circulation by 5-times. People would exchange any cash they had (and bank balances) for new dollars and be economically neutral. But bond holders would see the value of their holdings decrease by 80%.

Obviously, this approach would have negative side effects including impacting holders of any other dollar-denominated debt. Resulting in a huge benefit to large debtors (like real estate developers) and massive loss to savers (like retirees, pension plans and insurance companies).

If you don’t think a currency-swap is realistic, note that India recently abruptly declared most of their currency worthless and made everyone exchange high-value notes for a new currency. This demonetization was purportedly done for the purposes of flushing out black money avoiding taxation, but still resulted in the complete loss of value to anyone who didn’t exchange their high-value notes in time.[iii]

A Stealth Default

A synthetic or soft default is a simpler approach—just nationalize the debt. Instead of the government not repaying the outstanding debt, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) buys-up Treasury bonds.

Although the debt will continue to accumulate, it effectively becomes a closed loop system untethered from economic realities. The ever-increasing interest payments are simply returned to the Treasury.

- The Treasury issues debt to fund the government’s deficit spending

- The Federal Reserve “prints” as much money as required to buy the debt (as the United States’ central bank, they can just create money as needed)

- The Treasury continues making interest and principal payments to debt holders (mainly The Fed)

- The Fed returns the “profit” (i.e., interest payments) from their bond holdings back to the Treasury

- Rinse and repeat ad nauseum

The net result being the government no longer needs independent investors to purchase debt. No more worries about what interest rate outside investors will demand for the government’s increasingly risky paper.

Economic theory would say nationalizing the debt should have a similar impact to devaluing the currency. Each dollar should be worth less and less (i.e., an increasing rate of inflation) as more money is printed to buy the ever-expanding debt. Effectively spreading out the pain of (not) repaying the debt to all citizens.

And It Has Already Begun

If you are thinking this sounds familiar, that because it has already started. The Federal Reserve’s response to the Great Recession was a program dubbed Quantitative Easing (QE). The Fed bought nearly $4 trillion in U.S. Government debt and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) between 2008 and 2014.[iv]

Over eight years after the recession ended, the Fed finally started reducing the size of its balance sheet. Yet this effort to shed Fed-owned bonds was halted after only about 20% of the accumulated debt was run off. And now the Fed has started buying bonds again. As of October 9, 2019, the Feds balance sheet is at $3.9 trillion and growing (again).[v]

Although the Fed stopped QE efforts in 2014, they continued to buy Treasury securities and MBS to reinvest principal payments and rollover Treasuries as they mature. By not letting the level of Treasury holdings decrease as securities naturally mature, the Fed was (and is) effectively maintaining an accommodative monetary policy.

End Game

I believe this debt nationalization effort will never be announced as official policy. An official announcement would demonstrate weakness in the United States’ finances and would increase expectations for future inflation. More likely, the Fed will continue to look for excuses to increase its bond holdings without ever making it an official policy.

Just this past September we have seen the first excuse to grow the balance sheet again since the end of QE in 2014. A purported shortage of cash in the banking system led to a spike in overnight lending rates among banks. The Fed stepped in and again started to increase the size of their balance sheet to compensate. Although the Fed is adamant that this is not another round of QE. A rose by any other name…

Given the current low interest rates, the Fed will have little room to lower interest rates to stimulate demand when the next recession hits. They will quickly revert to the Great Recession playbook (as the European Central Bank has already done) and start buying up more Treasury securities again. Ballooning the Fed’s balance sheet and removing additional government debt from the open market.

During the Great Recession, the Fed eventually purchased Treasury securities of over $2 trillion[vi] which represented about 22% of the national debt at the beginning of the recession. If a new recession starts in 2020, and the Fed goes on a similar money printing/bond buying spree, it would take on an additional $5 trillion in Treasury securities (22% of $23 trillion).

It is not hard to see how this pattern of behavior quickly (in fiscal terms…a couple of decades) results in the Fed holding a majority of outstanding Treasury securities. Effectively nationalizing the national debt after just a couple of business cycles.

What Is Different Now

The United States has only run a budget surplus in 4 of the past 50 years[vii]. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects ever increasing deficit spending. Congress is unwilling to match revenue with spending.

So what? How is today different than the mid-1990’s when Perot ranted against run-away deficit spending? It has been 25 years or so and everything seems to have worked out okay.

True—there have been people warning about the national debt for many, many years, and low and behold, the sky has not (yet) fallen.

There are at least three significant differences between now and then:

- Demographics—ratio of workers to retirees and slower growth of population

- Political will—almost a complete lack of restraining force on increased debt

- Global equalization—U.S. economic dominance continues to shrink (normalize?) as other nations (particularly in Asia) grow at a faster rate, challenging the preeminence of the U.S. dollar

As the population of the United States continues to age there will be less people working, and paying taxes, relative to the number of older citizens collecting Social Security, Medicare and other government benefits. This further increases the challenge of aligning government spending with revenue. Even today, discretionary spending amounts to less than one-third of government expenditures.[viii]

Current CBO estimates show $1 trillion budget deficits every year going forward. Government spending is projected to exceed revenue by 4% of GDP in 2020 with the annual deficit increasing to nearly 9% of GDP in 30 years[ix].

As worrisome as these projections are, they may be overly optimistic. The CBO assumes steady GDP growth—with no future recessions—and no extraordinary spending (e.g., a war). Yet we just witnessed the damage the last recession did to government finances.

Plus, keep in mind these projections presume politicians allow the lower personal income tax rates contained in the 2017 TCJA to sunset as scheduled in 2025—bumping up estimated revenue for 2026 and beyond. If the current tax rates are made permanent, future deficits will be even larger.

What Should You Do?

Nationalizing the resulting national debt will be (is) the least bad of the available options for politicians who continue to put their reelection above the long-term financial security of the country.

It is safe to say this approach—the Fed buying up Treasury securities—cannot continue forever and therefore must end at some point (per Stein’s law: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop”).

It is hard to imagine a pleasant ending—for the country and its citizens.

I urge you to consider the following over the coming years:

- Apply critical thinking and skepticism to Fed’s actions that deepen its control of the economy and to politician’s proposals that further increase government deficits

- Prepare for an extended period of Fed-engineered low interest rates as they continue in their attempt to artificially stimulate economic growth…

- …but be prepared for a sudden inflation-spike once sediment shifts and people realize the Fed can’t continue buying debt forever

- Own wealth-producing assets (e.g., equity in companies with pricing power, rental real estate, etc.) that can maintain revenue/income and therefore have the potential to retain their value when an inflation shock hits—avoid long-term fixed income investments

[i] https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/histdebt/histdebt.htm

[ii] https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/pd/histdebt/histdebt_histo5.htm

[iii] https://www.strategy-business.com/article/What-Happened-after-India-Eliminated-Cash?

[iv] https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/fed-financial-statements.htm

[v] https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/current/h41.htm

[vi] https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/fed-financial-statements.htm

[vii] https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#2

[viii] https://www.cbo.gov/publication/55342

[ix] https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#1